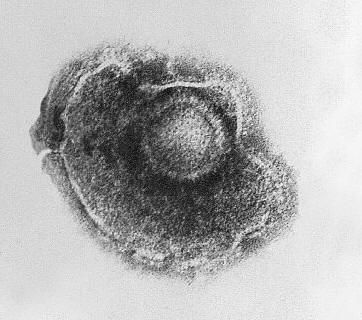

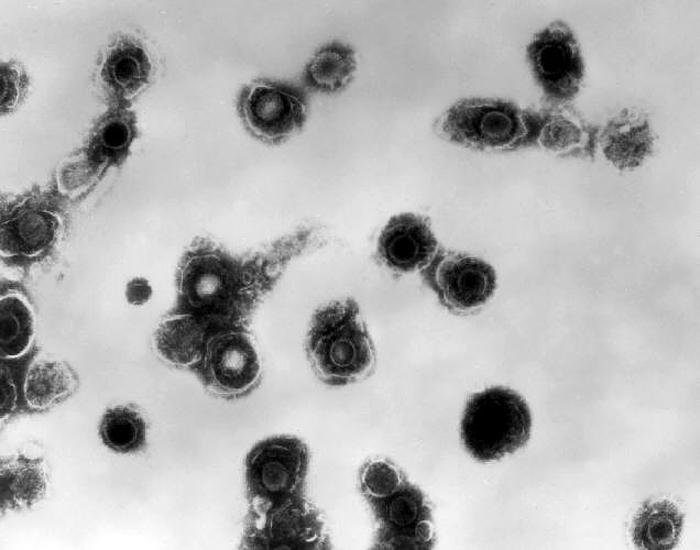

Varicella-Zoster VirusOverview: Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is an enveloped, double-stranded linear DNA virus with an icosahedrally arranged capsid, and a member of the Herpesviridae family, related to the Epstein-Barr virus, of the same subfamily (α-Herpesvirus) as the herpes simplex viruses (HSV-1 and HSV-2) (Figure 1). VZV virions are spherical and roughly 150 nm (nanometres) to 200 nm in diameter and possess a genome that is slightly less than 125000 base pairs in length (Cohen et al., 1998). The capsid is surrounded by a number of loosely associated proteins collectively known as the tegument; many of these proteins play critical roles in initiating the process of virus reproduction in the infected cell. The tegument is covered by a lipid envelope studded with glycoproteins that are displayed on the exterior of the virion. The known envelope glycoproteins (gB, gC, gE, gH, gI, gK, gL) correspond with those in HSV. VZV commonly causes chickenpox in children and both shingles and postherpetic neuralgia in adults. Figure 1. Electron micrograph of a varicella virus. Life Cycle and Clinical Infections: The virus is transmitted in fluids, primarily from coughing or sneezing (Figure 2). It can also be transmitted by skin contact or via contaminated air particles. Once the virus is inhaled, its infects the conjunctivae or the mucosae of the upper respiratory tract, and two to four days after infection, begins to proliferate in the regional lymph nodes of the upper respiratory tract. This results in the childhood disease varicella or chickenpox. Chickenpox is a highly contagious acute infection, which results in mild fevers, itching, fatigue, skin lesions, and blister-like rashes covering the whole body, but usually more concentrated on the face, scalp, and trunk (Figure 3). While the disease is usually mild, a very small proportion of children (1 in every 1000) develop VZV encephalitis – an acute, severe, neurological disease (Cohen et al., 1998). Figure 2. Transmission electron micrograph of varicella-zoster virions from vesicle fluid of patient with chickenpox. Figure 3. This photograph depicts the left shoulder region of a bedridden elderly male who was at first glance, thought to be suffering with a case of smallpox, which was subsequently determined to be a case of chickenpox. Viremia, or infection of the bloodstream, soon follows. About 14 to 16 days after infection, secondary viremia causes a second round of replication, this time mainly in the body's internal organs (mostly liver and spleen). This secondary viremia also is characterized by viral invasion of capillary endothelial cells and the epidermis, resulting in the characteristic vesicles of chickenpox. After primary infection of VZV, the virus spreads from mucosal and epidermal cells to nerve cells, especially the dorsal root ganglia, where it remains latent until reactivation later in life. The pathogen usually reactivates as a result of severe stress or immunosuppression, resulting in herpes zoster (more commonly known as shingles), a condition characterized by pain and renewed lesions. Despite a low rate of occurrence, herpes zoster infections are a major health and economic concern in some locations; Cheong et al. (2010) reported an annual cost of over $75 million in Korea, highlighting the economic, as well as health benefits of widespread vaccination. Zoster sine herpete is an infection associated with viral reactivation, causing patients to exhibit pain and motor weakness, but no visible skin lesions. In as many as 25% of shingles cases reported, acute facial paralysis may result. The pain in the areas affected by shingles is referred to as postherpetic neuralgia; this pain may become a chronic issue, persisting years after the infection has otherwise healed (Cohen et al., 1998). The risk of postherpetic neuralgia increases with age, and in extremely rare cases, the infection can lead to hearing problems, blindness, and death (Cheong et al., 2010). Pathogenicity: When VZV particle first encounters a targeted cell, it docks with cell surface proteins, in particular mannose 6-phosphate receptors. The viral envelope then fuses with the plasma membrane of the cell and the viral capsid containing the viral genome and tegument proteins enter the cytoplasm. The capsid then travels along a microtubule towards the nucleus where it docks with a nuclear pore. The viral DNA enters the nucleus through the pore and circularizes before replication. New viral capsids assemble in the nucleus and daughter genomes are taken into them. The capsids bud through the inner nuclear envelope gaining a temporary envelope that surrounds them during their stay in the perinuclear space. This envelope then fuses with the outer nuclear envelope and the now naked capsids progress through the cytoplasm until they bud into Golgi vesicles laden with viral proteins. This budding into the vesicle furnishes the developing virion with tegument proteins, an envelope and surface projections. The vesicle delivers the contained virion to the cell surface. The vesicle fuses with the plasma membrane and the new virus particle is free to infect another cell. Diagnosis and Identification: The infection is often readily identifiable due to characteristic rashes produced, but Tzanck smearing or culturing fluid from a vesicle can confirm the diagnosis. Early diagnosis of Zoster sine herpete can be achieved using PCR techniques or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing. Immunization:

VZV is readily preventable by

vaccination, with 80% to 90% of immunized subjects

exhibiting total immunity to chickenpox (Cheong

et al., 2010). In fact, since the

vaccine's introduction, there has been a

significant decline in varicella-related deaths

and hospitalizations. Vaccinated individuals who

do suffer an infection usually experience mild

symptoms. Treatment: VZV-associated infections can be treated by a number of drugs and therapeutic agents including acyclovir for the chickenpox, and famciclovir and valaciclovir for the shingles. Immune response can also be boosted by administering varicella zoster immune globulin or VZIG, but it is only administered when there is a risk of severe complications occurring. The virus is also susceptible to disinfectants, notably sodium hypochlorite. References: Cheong, H.J., Choi, W.S., Huh, J.Y., Jo, Y.M., Kim, W.J., Lee, J., Noh, J.Y., & Song, J.Y. (2010). In Press. Disease burden of herpes zoster in Korea. Journal of Clinical Virology, 47(7): 325-329. Cohen, J. I., Cox, E. Iofin, I., Reddy, S.M., & Soong, W. (1998). Varicella-Zoster Virus ORF32 Encodes a Phosphoprotein That Is Posttranslationally Modified by the VZV ORF47 Protein Kinase. Journal of Virology, 72: 8083-8088. |